Many incoming freshmen are shocked to find out how expensive college textbooks can be, especially if you’re taking a full course load. Textbooks have officially reached the stratosphere at $400 (new) and $300 (used) for a chemistry course book.

STEMMING the tide.

Data gurus at Priceonomics analyzed textbook data using University of Virginia’s textbook list for approximately 750 courses. In fall 2015, the top five disciplines with the highest average textbook cost per class were:

- Economics

- Languages

- Chemistry

- Physics

- Psychology.

On average, STEM related disciplines have the most expensive textbooks. Many can cost over $200 a pop. To add insult to penury, STEM books sell for proportionally the least amount of their original price while the relatively inexpensive humanities books retain more value.

High book prices also adversely influence choice. The U.S. PIRG report Fixing the Broken Textbook Market (2014), based on a survey of more than 2,000 students from more than 150 different campuses across the country, found that:

- 65% said they had decided against buying a textbook because it was too expensive.

- Nearly half (48%) said the cost of books had an impact on how many or which classes they took.

- Of those who had skipped buying a required book, 94% said they were concerned this would hurt their grade in that course.

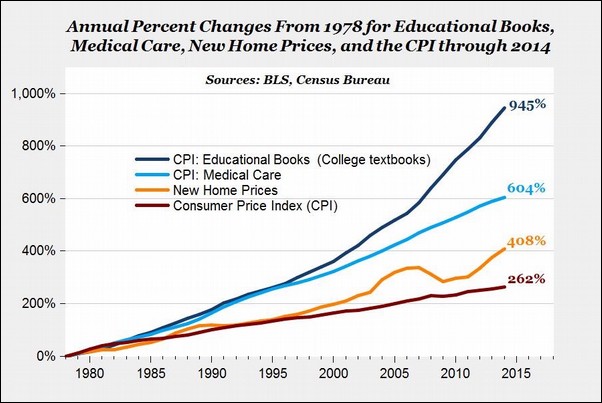

What goes up never comes down.

Paralleling increases in the cost of overall college attendance, PIRG’s 2016 report, Covering the Cost, reveals that the price of college textbooks continues to soar. Since 2006, the cost of a college textbook increased by 73%—over four times the rate of inflation. Students are a captive audience, which has allowed publishers to drive up prices to unsustainable levels.

Source: American Enterprise Institute (2015)

Estimates of student spending on textbooks vary. The College Board (2016) figures the average student spends around $1,200 a year on books and supplies. For those attending community college, this can be as much as 40% of total costs. The National Association of College Stores pegs textbook spending for 2016-17 at $662, less than in the past despite rising retail prices. One reason, they say, is the industry is moving away from printed textbooks to what they call “digital learning programs.”

So, what’s driving the price run-up?

Consider the following:

- Some professors are unaware of—or indifferent to—the cost of the books they assign. A few may require that students buy their own book. Choice of textbooks may not be left to instructors, however, if the department negotiates a “good deal” with the publisher.

- In rapidly changing fields (e.g., medicine and science), frequent revisions are necessary to keep content current. Many of these textbooks have limited applicability outside of the discipline, which drives up prices and lowers resale values.

- To a publisher, the professor is the customer not the student. According to PIRG, five publishers control 80% of the industry and competition is intense. Publishers sway professors with “niceties” such as free teaching editions, PowerPoint slides, and instructor guides.

- Publishers make no money from used textbooks. Faced with a dwindling number of new book sales, publishers have dramatically shortened publishing cycles. A California State Auditor report (2008) found that many revisions are cosmetic and unnecessary.

- Publishers bundle textbooks with other materials, such as CD-ROMS, flash cards, etc. that often aren’t used. Another trick is to publish books loose bound, which cannot be resold.

The next affordability frontier is digital. In many courses, students are required to purchase online materials with one-time digital access codes. A Student PIRG survey (2016) found the average cost of a stand-alone access code, purchased at a campus bookstore, is about $100. Across the colleges and majors analyzed, about a third of courses included access codes among the required course materials.

For better or worse, the camel’s snout is under the tent. Publishers are heavily pushing digital textbooks because they are cheaper than traditional textbooks and easier to update. While they save on printing costs, the real payoff (for them) is the codes are attached to an individual student account. Once activated, digital textbooks cannot be reused, shared, or sold. Like condoms, they’re designed for one use only.

Attention shoppers!

Students, you are not defenseless against the textbook titans. Here are a few tips:

- Buying used books and older editions is still the easiest way to save money on textbooks.

- Sites such as Chegg and Amazon, allow you to search for, buy, rent, and sell used textbooks, typically for less than half of the original sticker price.

- Compare prices before you rent or buy at sites like CampusBooks, TextSurf, SlugBooks, and BookFinder.

- Although limited in selection, thousands of no cost textbooks can be found at sites like Project Gutenberg, Open Book Project, and the Online Books Page.

- Ask your instructor to post the book title, ISBN, and cover image online before class starts so you can shop for the best deal before the stampede.

- Copies of textbooks are often kept for public access at the campus library.

- Look into textbook scholarships (Barnes & Noble offers up to $800 on some campuses).

- Check whether students at your school have set up a textbook exchange Facebook group.

- Split the cost with a friend and alternate photographing the chapters (probably not legal).

In 2015 the Affordable College Textbook Act was introduced in Congress (and re-introduced in 2017). The bill supports development of open textbooks, which allows anyone to access a textbook online or download it for free. A physical copy would cost about $20. Open textbooks could potentially save students billions of dollars without sacrificing quality. You can help raise awareness by asking your professors to adopt an open textbook for their course.

Higher education is a uniquely hidebound industry whose economics largely defy rational explanation.

~ Robert Reich, former U.S. Secretary of Labor

Learn more about this, and other interesting topics, in the Young Person’s Guide to Wisdom, Power, and Life Success.

Image credit: “Frustrated college student” by Todd Arena, licensed from 123rf.com (2017).